Water is the lifeline of Pakistan’s agriculture and rural economy. Almost 90% of the country’s freshwater withdrawals are directed to irrigation, making agriculture the single largest consumer of water. With such heavy reliance, irrigation water distribution, usage, and management require a strong legal and institutional framework. Over the years, Pakistan has developed a set of irrigation water laws that regulate allocation, distribution, dispute resolution, and canal management. However, challenges such as inequity, outdated frameworks, weak enforcement, and emerging climate-related pressures demand a rethinking of these laws. Understanding irrigation water laws, their evolution, and their shortcomings is essential for ensuring water productivity, sustainability, and equitable access.

Historical Context of Irrigation Water Laws in Pakistan

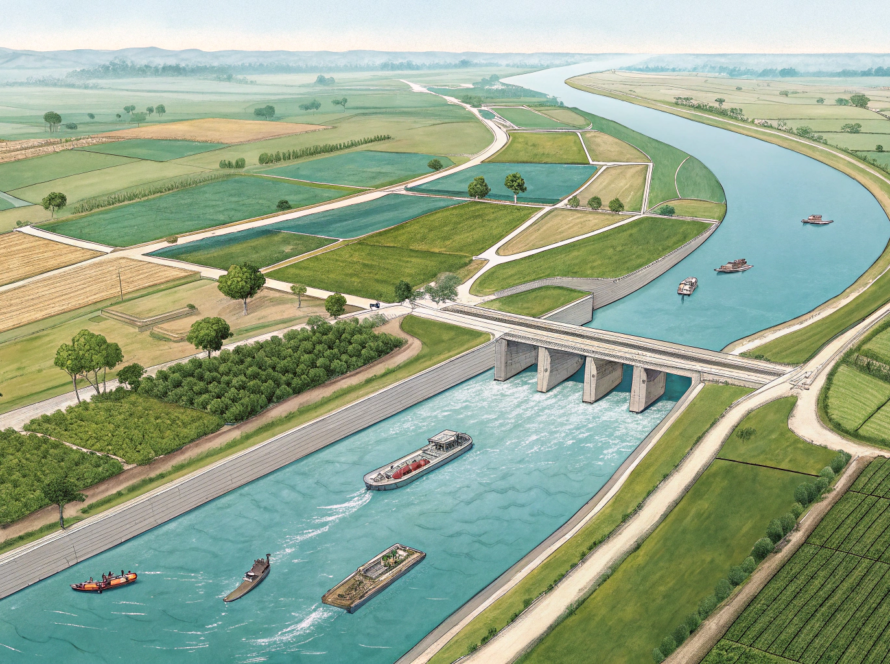

The roots of irrigation water laws in Pakistan lie in the colonial period, when the British built one of the world’s largest canal irrigation systems in the Indus Basin. To manage this massive infrastructure, legal instruments were created:

- Northern India Canal and Drainage Act (1873): This law regulated canal water distribution, drainage, and the rights of landholders. Even today, it remains the basis of many provincial irrigation acts.

- Punjab Minor Canals Act (1905): Designed to address management at the distributary and watercourse level.

- Punjab Tenancy Act (1887) and Land Revenue Act (1967): Indirectly linked, as water allocation was tied to land records.

After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, these colonial-era laws were retained and slightly modified. The provinces gradually enacted their own irrigation acts, yet the foundations remained largely unchanged.

Key Irrigation Water Laws and Frameworks

1. Provincial Irrigation and Drainage Acts

- Provinces such as Punjab (1997), Sindh (1997), and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (1997) passed their irrigation and drainage acts.

- These acts created Irrigation and Drainage Authorities (IDAs) to oversee canal systems, promote efficiency, and encourage participatory irrigation management.

- They aimed to decentralize management by empowering Area Water Boards and Farmer Organizations (FOs).

2. Indus Waters Treaty (1960)

- Though international in scope, this treaty between Pakistan and India is critical for Pakistan’s irrigation.

- It allocates the waters of the eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) to India and the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab) to Pakistan.

- This treaty sets the foundation for water availability in Pakistan, upon which internal irrigation laws operate.

3. Water Apportionment Accord (1991)

- A landmark agreement among provinces on how the waters of the Indus system are shared.

- Ensures equitable allocation but has been controversial, particularly during drought years when provinces accuse each other of receiving less than their share.

- Sindh often raises concerns about upstream diversions, while Punjab stresses the need for reliable distribution to meet food security demands.

4. Canal and Watercourse Laws

- Rules governing warabandi (rotational water distribution), maintenance of canals and watercourses, and penalties for tampering with water outlets.

- These laws are vital for managing irrigation at the farmer level, but enforcement remains a challenge.

Why Irrigation Water Laws Struggle in Pakistan

Despite having a strong legal foundation, the effectiveness of irrigation laws has been limited due to several reasons:

- Outdated Colonial Frameworks:

Many laws were designed for a time when population pressures, groundwater exploitation, and climate change were not as severe. Today’s challenges require modern legal tools, not colonial-era fixes. - Weak Enforcement:

- Illegal water diversions and tampering with outlets are common.

- Small farmers often lack the power to challenge influential landlords who manipulate flows.

- Groundwater as a Legal Grey Area:

- Groundwater extraction, which supplies almost 40% of irrigation water, is poorly regulated.

- Farmers can install tube wells without restriction, leading to over-extraction, falling water tables, and quality deterioration.

- Inequity in Access:

- Head-end farmers often get more water, while tail-end farmers suffer shortages.

- Warabandi laws exist but monitoring and penalties are weak.

- Fragmented Institutional Setup:

- Federal and provincial agencies often overlap.

- Coordination between irrigation departments, water authorities, and agriculture departments is weak.

Emerging Challenges for Irrigation Laws

- Climate Change: Changes in river flows, glacier melt, and erratic rainfall patterns create new pressures that current laws don’t address.

- Waterlogging and Salinity: Canal seepage and poor drainage require integrated management, but legal instruments are silent on this.

- Digital Agriculture: Remote sensing and GIS tools for monitoring irrigation are available, but their legal use for dispute resolution is not yet institutionalized.

- Transboundary Pressures: Beyond the Indus Waters Treaty, increasing upstream projects in India and China require adaptive laws.

Pathways for Reforming Irrigation Water Laws

To make irrigation water laws responsive to present and future challenges, several reforms are necessary:

- Legal Recognition of Groundwater:

- Introduce groundwater legislation that regulates pumping, ensures sustainable recharge, and promotes conjunctive use with surface water.

- Licensing and pricing mechanisms can help reduce overuse.

- Strengthening Warabandi Enforcement:

- Modernize monitoring through digital meters, satellite imagery, and community-based reporting.

- Establish stronger penalties for tampering with water distribution.

- Participatory Irrigation Management:

- Empower Farmer Organizations (FOs) with real decision-making power.

- Provide legal protection to smallholders to ensure fair representation.

- Integration with Climate Policy:

- Laws should mandate climate-resilient irrigation practices, such as lining watercourses, promoting drip and sprinkler systems, and enhancing recharge structures.

- Institutional Harmonization:

- Create a unified National Water Regulatory Authority to oversee irrigation, groundwater, and drainage across provinces.

- Ensure provincial laws align with federal water policy.

- Dispute Resolution Mechanisms:

- Strengthen water tribunals for faster resolution of inter-provincial and intra-provincial disputes.

- Encourage alternative dispute resolution methods through farmer committees and mediation.

Conclusion

Pakistan’s irrigation water laws have served as the backbone of canal management for more than a century, yet they are increasingly unfit for modern realities. The heavy reliance on colonial-era laws, coupled with weak enforcement and poor regulation of groundwater, has created inefficiencies and inequities in the system. Climate change and population growth make reform even more urgent. By modernizing laws, integrating climate and digital tools, and ensuring equitable access, Pakistan can transform its irrigation system into one that sustains productivity, supports food security, and promotes fairness across regions.

Strong and updated irrigation water laws are not just about rules and penalties—they are about ensuring that every drop of water is used wisely, equitably, and sustainably for generations to come.