Water is one of the most precious resources in Pakistan’s agriculture, yet its management often suffers from inefficiency and disputes. Accurate gauging and flow measurement are the backbone of fair water distribution, effective irrigation scheduling, and long-term water governance. Without proper measurement, we cannot assess how much water is diverted, how much reaches the farmer’s field, and how much is lost in transit. Unfortunately, in Pakistan, the system of water measurement is outdated, inconsistent, and in many areas completely absent. This leads to inefficiency, inequity, and mistrust between water users and managers.

This column explores the fundamentals of gauging and flow measurement, the challenges faced in Pakistan, the consequences of weak measurement systems, and the modern solutions available for improving water governance and irrigation efficiency.

📏 Importance of Gauging and Flow Measurement

Accurate water measurement is not just a technical necessity—it is a pillar of water governance. Its importance can be summarized in several key dimensions:

- Fair Water Distribution

In canal systems, farmers depend on reliable water supplies for their crops. Flow measurement ensures equitable allocation of water among head, middle, and tail-end farmers. Without gauging, tail-enders often receive less than their rightful share, creating disputes and inequity. - Irrigation Efficiency

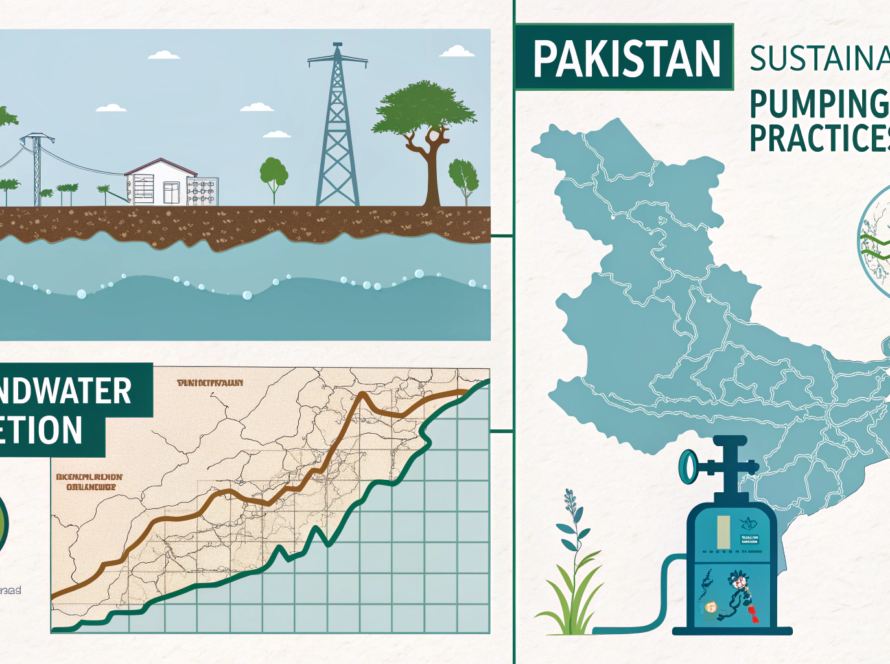

Measurement helps identify water losses through seepage, leakage, or unauthorized withdrawal. By knowing how much water enters and exits a section, managers can take corrective actions. - Groundwater Sustainability

Flow data is essential to monitor how much surface water is delivered and how much groundwater is being over-extracted as compensation. - Water Pricing and Accountability

Any system of water charges, service fees, or volumetric pricing depends on accurate measurement. Without it, both overuse and underpayment occur. - Planning and Forecasting

Historical data from gauging stations informs water balance studies, hydrological models, and irrigation scheduling. This allows governments to better plan for droughts, floods, and long-term resource sustainability.

⚠️ Current Challenges in Pakistan’s Water Measurement System

Despite the critical importance of flow measurement, Pakistan faces numerous obstacles in this domain:

- Outdated Infrastructure

Many canal head regulators, distributaries, and minors still use century-old structures built during the colonial period. These were not designed for modern precision needs. - Manual Observation

Gauging is often performed manually, using staff gauges or float methods, which are prone to human error, manipulation, and inconsistency. - Limited Coverage

Thousands of minors and watercourses lack any formal measurement system, making it impossible to track flows at the field level. - Lack of Calibration

Many existing structures are not properly calibrated, meaning the recorded discharge does not accurately reflect actual flow. - Political and Institutional Weakness

Flow data is sometimes manipulated for political reasons, leading to mistrust among farmers. Weak enforcement and corruption exacerbate the problem. - Technological Gap

The adoption of modern tools like ultrasonic meters, telemetry systems, or satellite-based monitoring remains slow due to lack of investment and technical capacity.

🔍 Methods of Flow Measurement

Flow in irrigation systems can be measured by a variety of methods, each with strengths and limitations:

- Staff Gauges and Rating Curves

The simplest method, involving stage-discharge relationships. It is inexpensive but requires proper calibration. - Weirs and Flumes

Standard structures such as Parshall flumes or V-notch weirs provide relatively accurate measurement. However, they require proper design and maintenance. - Velocity-Area Methods

Using current meters or floats, discharge is estimated by multiplying velocity with cross-sectional area. Practical but time-consuming. - Modern Sensors and Telemetry

Ultrasonic flow meters, radar sensors, and automated telemetry systems can provide real-time and highly accurate data. These systems also enable remote monitoring and data archiving.

🌾 Impacts of Poor Measurement

When flow measurement is weak or absent, the consequences are severe:

- Inequity in Water Distribution: Head-end farmers capture more water, leaving tail-enders deprived.

- Low Water Productivity: Without accurate delivery records, water productivity (crop per drop) cannot be assessed or improved.

- Groundwater Overuse: Farmers compensate for uncertain canal supplies by pumping groundwater excessively, leading to declining water tables and quality deterioration.

- Conflict and Mistrust: Farmers lose trust in irrigation departments when they feel deprived due to misreported flows.

- Weak Policy Implementation: Any reform—such as water pricing, rotational schedules (warabandi), or climate adaptation—fails without reliable data.

✅ Solutions and the Way Forward

Strengthening gauging and flow measurement in Pakistan requires both technical and institutional interventions:

- Rehabilitation of Infrastructure

Modernization of canal headworks, distributaries, and minors with calibrated structures (flumes, weirs, automatic gates). - Adoption of Smart Technologies

Deployment of ultrasonic and electromagnetic flow meters, telemetry systems, and IoT-based sensors for real-time monitoring. - Capacity Building

Training irrigation staff and farmers on flow measurement techniques and the importance of reliable data. - Community Participation

Water User Associations (WUAs) can monitor flows jointly with irrigation departments, ensuring transparency and fairness. - Policy and Legal Framework

Mandating measurement and transparent reporting of flows under irrigation laws. Data should be publicly accessible. - Integration with Remote Sensing

Combining ground-based gauging with satellite-based evapotranspiration (ET) and flow monitoring to create a comprehensive water accounting system. - Pilot Projects and Scaling

Starting with pilot schemes in major canal commands, followed by scaling across the Indus Basin, can demonstrate success and build farmer confidence.

🌍 Conclusion

Gauging and flow measurement may sound like a purely technical exercise, but in reality, it is at the heart of water governance, agricultural productivity, and social equity. Without accurate measurement, we cannot ensure fairness, efficiency, or sustainability in Pakistan’s irrigation systems. By modernizing infrastructure, embracing technology, and fostering transparency, Pakistan can transform its water management into a system that serves both farmers and future generations.

Accurate measurement is not just about numbers—it is about justice, sustainability, and resilience. The time has come to make gauging and flow measurement the cornerstone of irrigation reform in Pakistan.