Water is the backbone of Pakistan’s agriculture, but its availability and distribution are far from equal. While some farmers receive abundant canal water at the head of distributaries, others struggle with limited supplies at the tail. In many cases, those deprived of surface water turn to groundwater. Yet, access to groundwater also varies—some can afford deep tube wells, while others rely on shallow, poor-quality water or costly purchases from neighbors. This imbalance raises serious concerns about equity, sustainability, and long-term productivity of our agricultural system.

This column explores canal and groundwater equity issues, their drivers, consequences, and possible solutions at different spatial scales: farm, community, command area, and national level.

1. Understanding Equity in Water Distribution

Equity in water management does not mean that every farmer receives the same amount of water, but rather that water should be fairly allocated according to need, landholding size, cropping patterns, and local conditions.

- Canal water is distributed under a rotational system (warabandi), intended to provide farmers with equal opportunity to irrigate their land.

- Groundwater has emerged as a buffer against canal shortages, but it is privately owned and heavily dependent on economic capacity.

The challenge is that inequity arises both within and across different levels of water distribution.

2. Canal Water Equity Issues

(a) Head-Tail Disparities

- Farmers at the head reaches of canals often receive more than their share, leaving tail-end farmers with insufficient water.

- Tail farmers resort to over-pumping groundwater, increasing their costs and worsening regional imbalances.

(b) Warabandi Limitations

- While the warabandi system is based on equal time allocation, in practice, political influence, corruption, and weak enforcement distort allocations.

- Farmers with more power often manipulate canal outlets to secure higher flows.

(c) Maintenance and Conveyance Losses

- Poor maintenance of canals and watercourses means that conveyance losses (30–40%) disproportionately affect farmers farther downstream.

3. Groundwater Equity Issues

(a) Unequal Access

- Wealthy farmers install private tube wells (sometimes >300 feet deep) with powerful pumps.

- Smallholders often depend on shared wells or purchase water at high rates, eroding profitability.

(b) Energy and Cost Barriers

- Electricity shortages and diesel costs make groundwater pumping more expensive for small farmers.

- Large farmers often enjoy subsidies or informal access to cheap energy sources, deepening inequities.

(c) Groundwater Depletion and Quality

- In many areas (e.g., Punjab and Sindh), excessive pumping has lowered water tables.

- Poor farmers cannot afford to deepen wells, and they are left with saline or brackish groundwater, further widening inequality.

4. Equity Issues Across Spatial Scales

(a) Farm Scale

- Within a farm, poor land leveling causes unequal irrigation across fields, with some areas waterlogged and others under-irrigated.

(b) Community Scale

- Villages often have internal power hierarchies. Larger landowners exert political and financial control, accessing both canal and groundwater resources more easily.

(c) Command Area Scale

- Across canal command areas, distributaries and minors experience inequity due to poor design, lack of enforcement, and unequal infrastructure upgrades.

(d) National Scale

- Provinces (Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) contest canal water allocations under the 1991 Water Apportionment Accord.

- Similarly, groundwater depletion is more severe in Punjab due to its high pumping, whereas Sindh faces more salinity issues. This creates regional inequities in agricultural productivity and water security.

5. Consequences of Inequity

- Reduced Productivity: Tail-end farmers suffer lower yields due to insufficient or poor-quality irrigation water.

- Economic Inequality: Water inequity reinforces class differences, with smallholders trapped in cycles of debt.

- Over-Extraction: Dependence on groundwater increases, accelerating depletion and salinity.

- Social Conflicts: Disputes over canal water turn into local conflicts, sometimes violent.

- Policy Failure: Lack of inclusive management erodes trust in irrigation institutions.

6. Pathways to Solutions

(a) Improving Canal Water Equity

- Strengthen Warabandi Enforcement: Transparent monitoring using remote sensing and digital flow meters can reduce manipulation.

- Canal Rehabilitation: Lining distributaries and watercourses can minimize seepage and losses.

- Participatory Irrigation Management (PIM): Empower water user associations to ensure fair distribution at the community level.

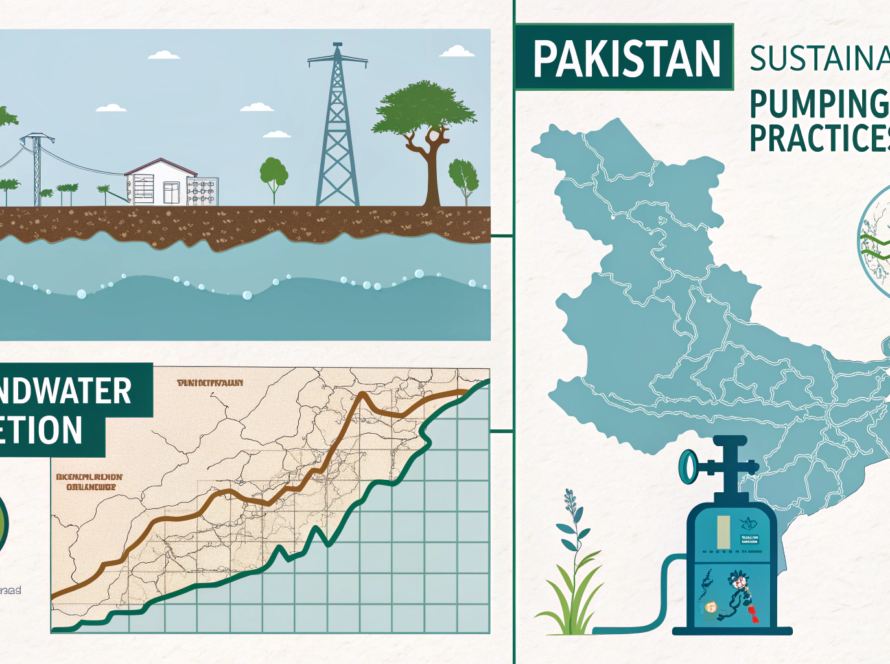

(b) Ensuring Groundwater Equity

- Regulation of Groundwater Pumping: Introduce licensing and metering to prevent over-extraction.

- Community Tube Wells: Install shared tube wells with fair pricing systems for smallholders.

- Energy-Efficient Irrigation: Promote solar pumping systems and efficient irrigation methods (drip/sprinkler) to reduce pumping costs.

(c) Integrated Canal-Groundwater Management

- Treat surface and groundwater as a single resource (conjunctive use) to balance inequities.

- Encourage policies where canal water allocations are adjusted based on groundwater availability in specific regions.

(d) Policy and Governance Reforms

- Strengthen the Indus River System Authority (IRSA) to monitor inter-provincial allocations.

- Introduce data-driven water governance using GIS, remote sensing, and IoT-based monitoring tools.

- Ensure that reforms prioritize smallholder farmers who are most vulnerable to inequities.

7. Way Forward

Equity in water distribution is not only a moral issue but also a foundation for sustainable agriculture and rural stability. Addressing head-tail disparities, regulating groundwater, and empowering communities can help bridge the gap between the “water-rich” and the “water-poor.”

A shift is needed from a supply-driven system to a governance-driven system—where transparency, accountability, and technology play central roles. Only then can Pakistan move toward fair, efficient, and sustainable water management, ensuring that every farmer—regardless of landholding size or location—has the opportunity to prosper.